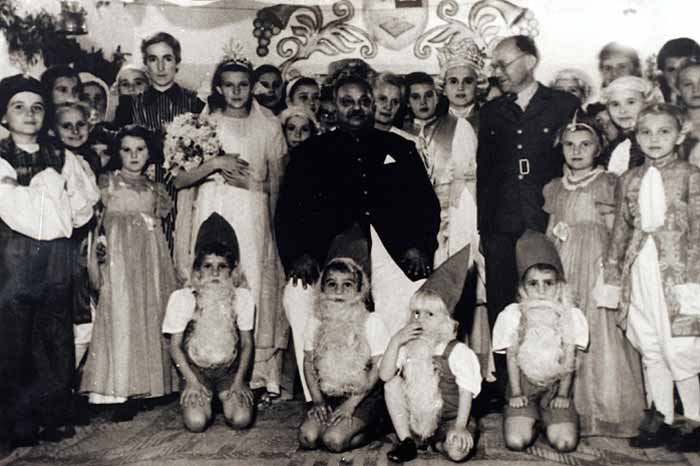

The Maharaja of Nawanagar with Polish orphans, Jamnagar: photo - CSPA

The Warsaw City Council passed a resolution on Friday in favour of the motion, following a campaign led by the Poland-Asia Research Center (CSPA).

A square in the Ochota district of central Warsaw has been chosen in honour of the late Indian prince, who died in 1966.

Owing to the difficulties in pronouncing the prince's full name - Jam Sri Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji Jadeja – it has been decided that the site will simply be called "the Square of the Good Maharaja."

Born in 1895, the monarch served as the Maharaja of Nawanagar from 1933 to 1947.

Nawanagar, which is today a part of north western India, was then one of the 565 princely states that were technically - although not in practice - independent from British rule in India.

The future ruler was educated at a boarding school in Great Britain, and his uncle, the previous Maharaja of Nawanagar, had been one of England's most celebrated cricketers.

A Saviour During the Second World War

After war broke out in September 1939, the maharaja was chosen as a member of Winston Churchill's Imperial War Cabinet.

His role in helping the Polish orphans came about as a result of the highly awkward alliance between the Western Powers and Soviet Russia.

Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia had divided up Poland in 1939, and in the Russian partition, several hundred thousand Poles – including women and children - were deported by Stalin to the depths of the Soviet Union.

However, when Hitler turned on his Russian ally, launching Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Stalin was compelled to make an alliance with Great Britain and Poland - the Polish government-in-exile was in London at this time.

Stalin announced an amnesty for his Polish prisoners, and the enormous task of attempting to transport the scattered captives out of the Soviet Union was set in motion.

General Wladyslaw Anders, himself freshly released from captivity, began forming a prospective army of Polish soldiers from the deportees.

The Maharaja of Nawanagar became a rallying figure in solving the plight of the many children and women caught up in the conflict.

He was the first Indian to offer to help Polish children who had been deported to Siberia, Kazakhstan and elsewhere.

Premises by the maharaja's summer palace at Balachadi, on the coast of Nawanagar, were prepared in cooperation with the Polish government-in-exile, and as many as 500 orphans were transported there.

Speaking in November 1942, the maharaja expressed his hopes that in "the beautiful hills beside the seashore, the children will be able to recover their health and to forget the ordeal they went through.”

The children remained there throughout the war, and they came to call the prince “Bapu” (father). A school was set up at the site, run by delegates of the Polish government-in-exile.

Meanwhile, other Polish children found refuge in Africa and New Zealand, (the latter thanks to the intervention of New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser).

A second settlement of over 5000 displaced Poles was also created in the Indian principality of Kolhapur, at Valvivade, where Poles of all age-groups found refuge.

Full Circle

Many of the adult deportees – likewise the soldiers of General Anders - did not return to Poland after the war, owing to the installation of a communist government in the country.

However, a considerable number of the orphans did resettle in their native land.

Nevertheless, the deportations to Siberia, which had been carried out by the Soviet government, were a taboo subject in communist Poland.

As a result of this, the maharaja was not honoured by the authoriries of communist Poland.

The moving spirit behind the recent campaign has been Krzysztof Iwanek of the Poland-Asia Research Center.

Cooperating with the Association of Poles in India 1942-1948, the CSPA achieved its first goal in February this year, when the Indian prince was posthumously awarded the Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit by President Bronislaw Komorowski.

Krysztof Iwanek hopes that the maharaja's good deeds will now hold a permanent place in Polish historiography.

Nick Hodge